Perspective for the artist (text and sketches by Peter van Stigt)

The world is three-dimensional. And, in order to capture this in a flat piece of artwork, the artist has to work according to a set of rules. The rules of ‘perspective’. In an effort to explain the phenomenon of ‘prespective’ to the layman with aspirations to become an (aviation) artist, this article was born. Because creating a three-dimensional composition through perspective is perhaps the most important aspect of creating 'The (W)right Stuff' on a flat surface.

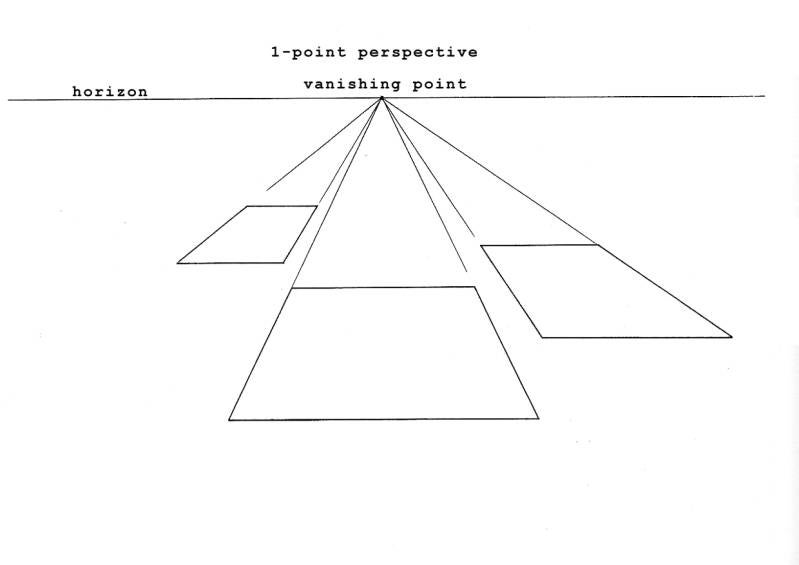

Single-point perspective

Everyone at one point or another has crossed a railroad track and stood still on the middle of it, when the coast was clear, of course. Looking along the track, it seemed to disappear to one single point at the horizon. This is the 'Mother of all perspectives' that all of us know so well. And it immediately explains a few elements that keep emerging when perspective becomes more complicated. Two of those elements are the horizon (H) and that single point on it: the vanishing point (VP). Perspective as seen in the railroad track is called single-point perspective (1PP).

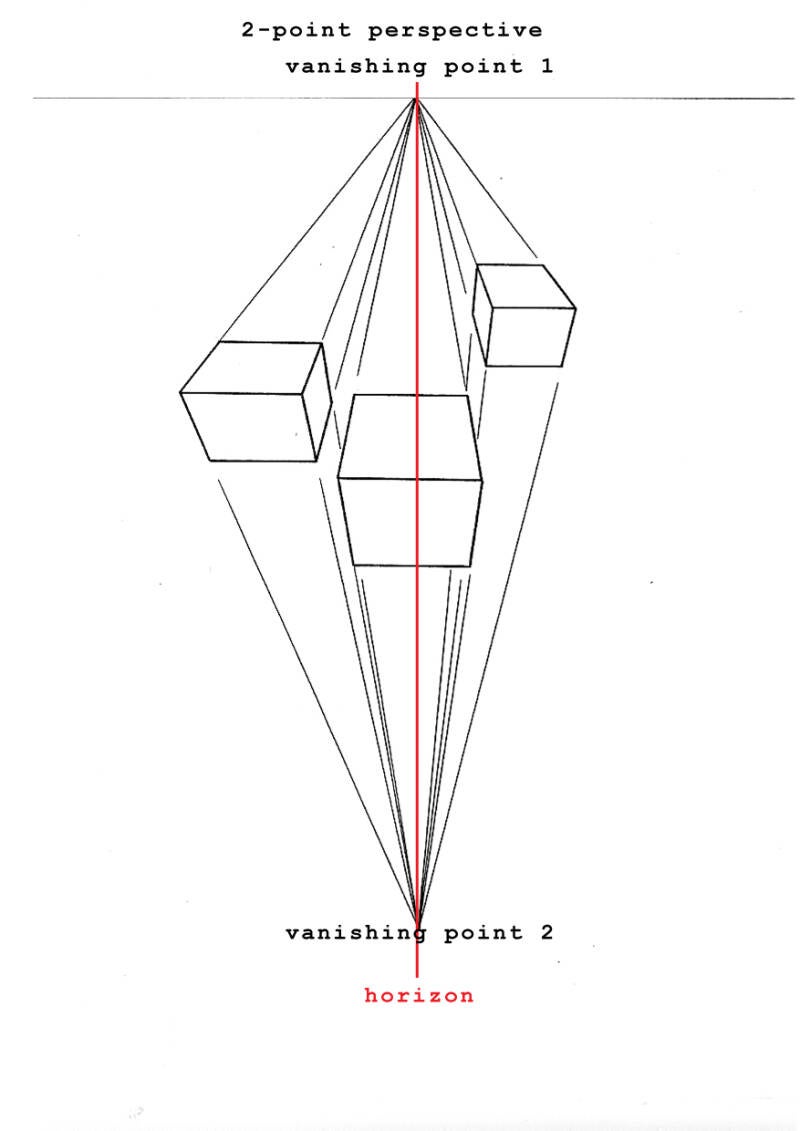

Two-point perspective

Just as all of us have witnessed the single-point perspective on that railroad track, we have all waited in our cars in front of a crossroads. Looking right and left to see if the coast was clear again, we unknowingly witnessed the same thing as on that railroad track... times two. Two roads, each running to their own vanishing points at a single horizon. The horizon is the same, but this time there are two VP's, one for each road. You guessed it, this is called two-point perspective (2PP) . Now, in this three-dimensional world it is not only a matter of a real horizon. The human imagination is able to produce an imaginary horizon complete with VP's, that can be tilted any way if so desired. In other words: a two-point perspective does not necessarily exist in a horizontal way but also in a vertical one and all the degrees in between, especially in moving subjects.

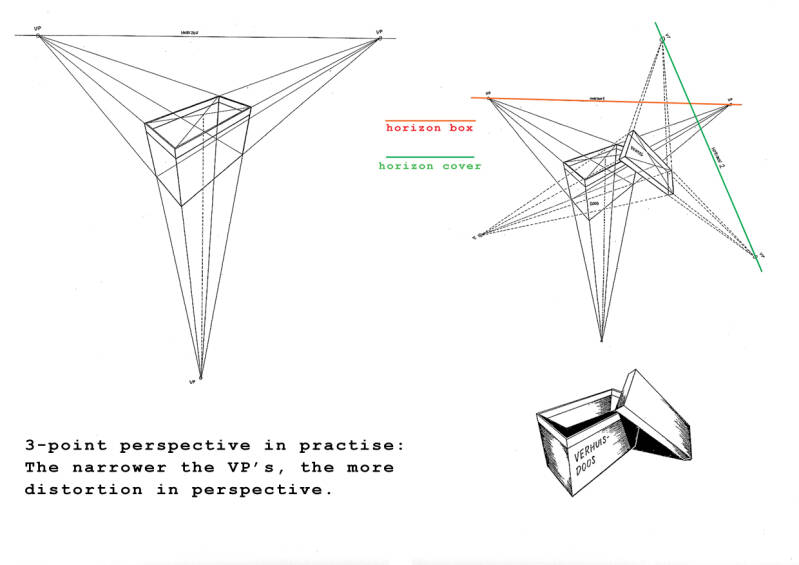

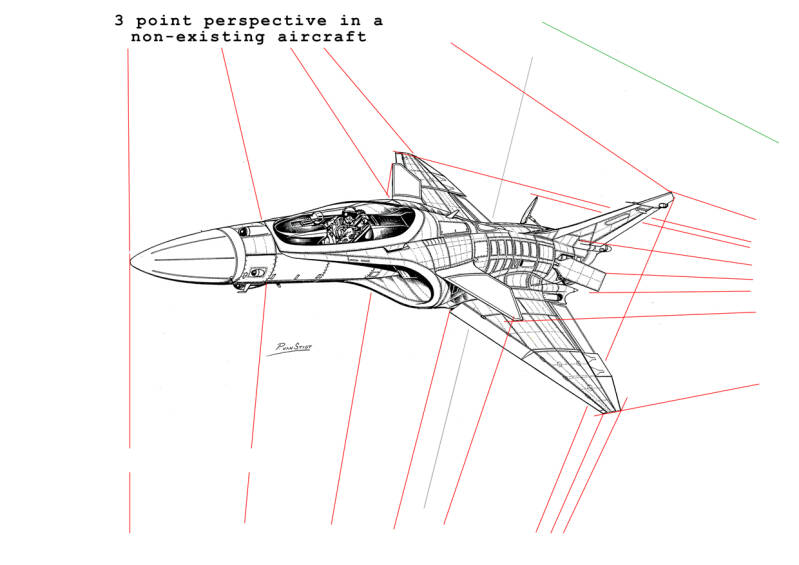

Three-point perspective

In 1997, when the Twin Towers were still standing, I was fortunate to oversee Manhattan while standing on the terrace on one of them. Maybe many of you have done the same. And, what we saw were many skyscrapers and other buildings, the Hudson and East River with their bridges. Examining one of the nearer skyscrapers, we witnessed the next step in the three dimensions: the upper surface was a square for example. Putting imagination to work, one could see the contours of that square and extend each of the four lines making up that square all the way to the horizon, very much like that crossroads. Two lines go to the left and form a VP, the two others disappear to the right on to the same horizon. But, looking down, there seemed to be a third set of lines, VP and another horizon. If imagination was still working, one could see the skyscraper going on below the ground surface (like the China Syndrome) and disappear to again a single point which is positioned on its own vertical horizon. Enter the three-point perspective (3PP). Looking down like this is called bird's eye view. Turn this whole scenery 180 degrees around and you will have a frog view of a floating skyscraper upside down. Drawing an object transparently, with all those work-lines (WL) to their VP on imaginary horizons in a sketch provides you with a CadCam-like image.

In practice

Take a shoe box and unleash the 3PP on to it. Start sketching, draw those worklines, vanishing points and horizons. Every line in the box's contour is a workline. Now take of the box cover and let it lean on the box in a casual, diagonal manner. Search for the cover's contour worklines, find their vanishing points and their own horizon. That's a whole new set of 3PP. This does not make the box + cover a 'six-point perspective' but merely two times 3PP, each requiring their own attention. The bottom line is adding a new subject to the scenery is adding a new 3PP. In practise: each aircraft added in a dogfight scenery means an extra 3PP. When the plane launches a missile that curves upward to its target, that's again an extra set of 3PP...

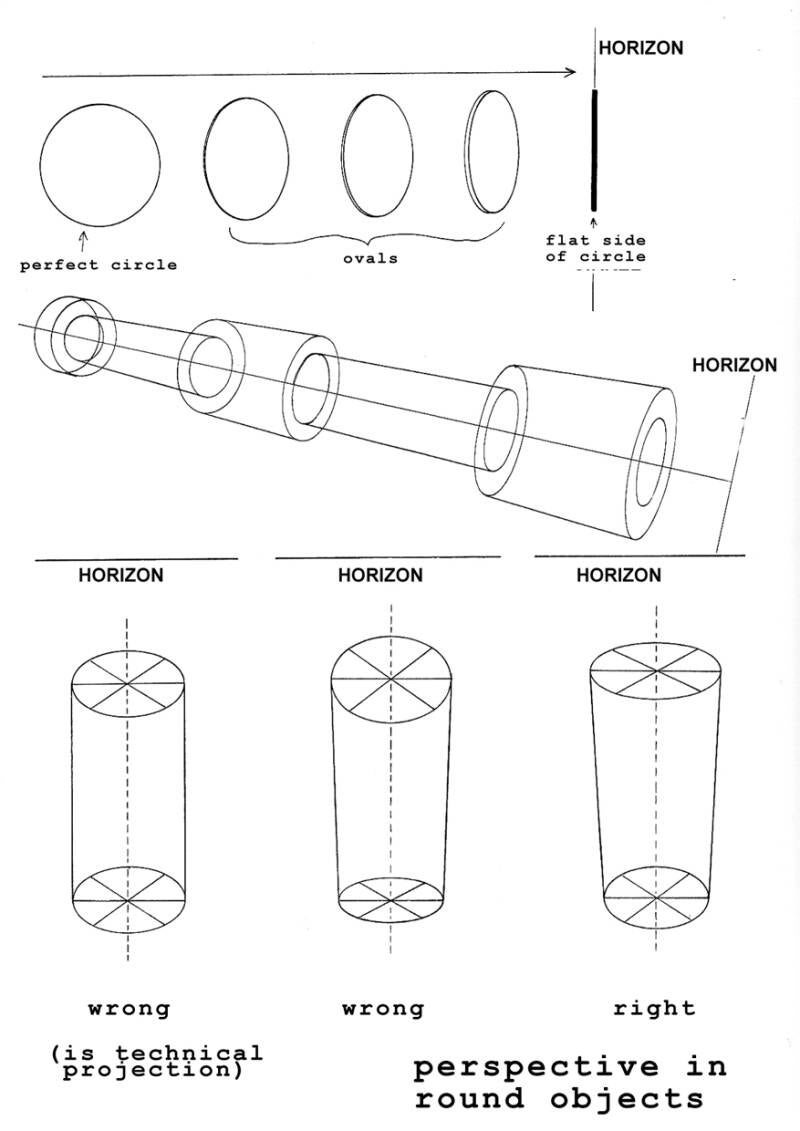

Think basic

Now that we have all elements of the 3D scenery in place, we have to remember that not all objects are square or symmetrical. Here comes the hard part. Most objects have a complicated form, consisting of several shapes. The trick is to recognise basic shapes in a complicatedly formed object. Cubes, boxes, pyramids, balls, eggs, cylinders, cones and triangles can be seen by the trained eye. A sedan car is basically a large box with a small one on top of it. Half way through and half way under the big box's cross-section run two cylinders, one in the front and one in the back. Those cylinders are broken up into four shorter ones. These form the car's wheels. A Dassault Mirage III fighter is basically a cylinder with a cone at the front, a large horizontal triangle underneath and a smaller vertical triangle on top of the cylinder's back. All built up in a sketch using three-point perspective. Observing like this is a way of live, requiring a lot of practice.

Perspective in perspective

Mastering the art of perspective is not something to underestimate. All too many artists (including famous ones like Vincent Van Gogh) take it a bit too lightly. A common mistake is to sketch the worklines exactly parallel to each other. This is not perspective but 'projection' as used in technical drawing. Or, the worklines run wider apart when running to the back instead of to a single vanishing point. That's the world upside down. Another faulty use of perspective is placing an object with a mild perspective (like taken with a telephoto lens) too big in the composition, or a subject with great perspective (wide-angle lens effect) too small in that same image. There is a rule to this: when an object is actually huge (like a skyscraper), use lots of perspective, a small subject in a large scenery should have a mild one.

Perspective in lighting

Not only the object itself is subject to perspective. The lighting and shading is bound by the same rules. The main source of light in our world is the sun. Basically the sun can be seen as a vanishing point where light beams end up in, because this light source is very, very far away and thus small. When a 3D object is blocking the sun at some point, it will produce a shadow on the surface it is standing on for example. Finding the light and shadow portions on and around an object means sketching worklines from the sun to each edge and corner of that object and its surrounding. Doing this accurately with that Mirage III fighter sitting on the tarmac, provides us with highlights more or less on the top surfaces of wing and fuselage, getting darker when getting lower in the curves and producing a shadow on the concrete below. This shadow consists of a large triangle with a narrow and pointy smaller triangle in front of it, all built up in three-point perspective.

Bring it all together

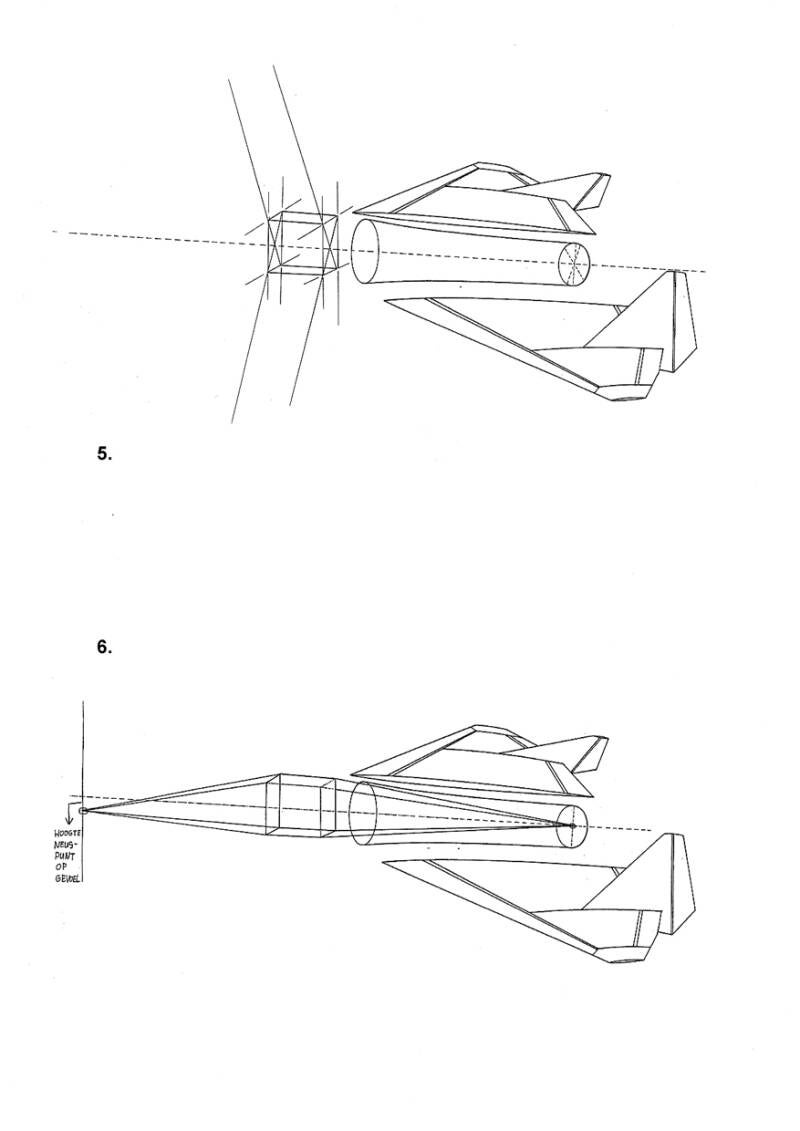

When we finally have mastered the art of perspective, we gain an extra sense of freedom. You can use this phenomenon to not only accurately sketching existing objects, but also producing forms that do not exist. You can act as a designer, using your imagination you can come up with your own state-of-the-art stealth fighter. Start simple, add more complexity and draw in the final shapes and curves at the latest possible moment. Pay extra attention to sketching oval shapes because that is what planes consist of for more than 50%. Sketch a background, cut out the plane shape with your scissors, move it around the background and let all pieces of the puzzle fall into place.

Independence

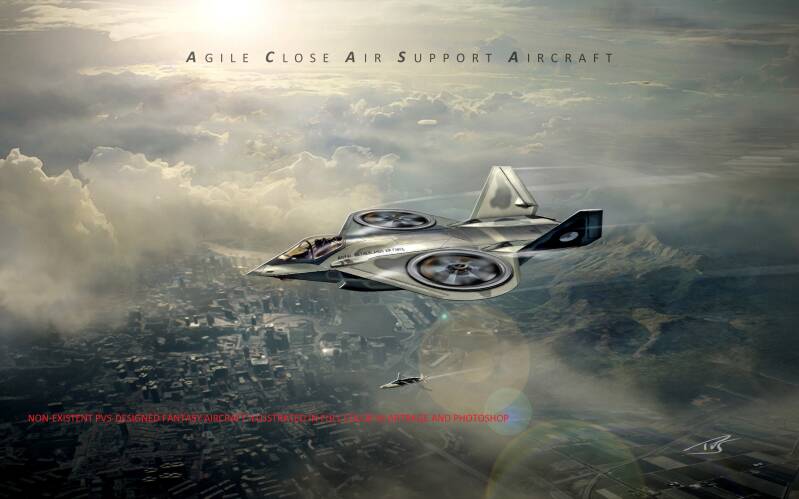

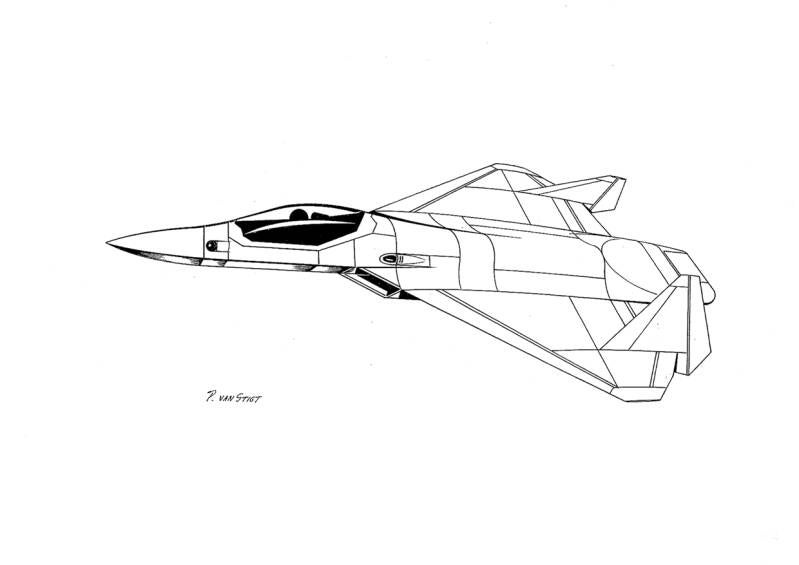

At one point I decided to come up with my own answer to the European Delta/Canard fighters of today. I called it MANTA, an acronym for Multirole Aircraft of Natural Technology Aerodynamics. As the design progressed the complexity of details did too. Drawing the thing in perspective (after I had produced a three-view drawing) became a real challenge. Only then I could see the aerodynamics taking shape. Wing roots, intakes, area ruling, speed brakes, canopy were almost dictating themselves to their respective shapes. Thinking about internal systems and their accessibility resulted in a lot of panels and hatches. For the purpose of this article, MANTA is shown with some of the worklines still in place and flying over a schematical background with its own perspective MANTA illustrates the independence and power to create from your own mind without an example. When executed the right way, perspective gives the aviation artist wings...

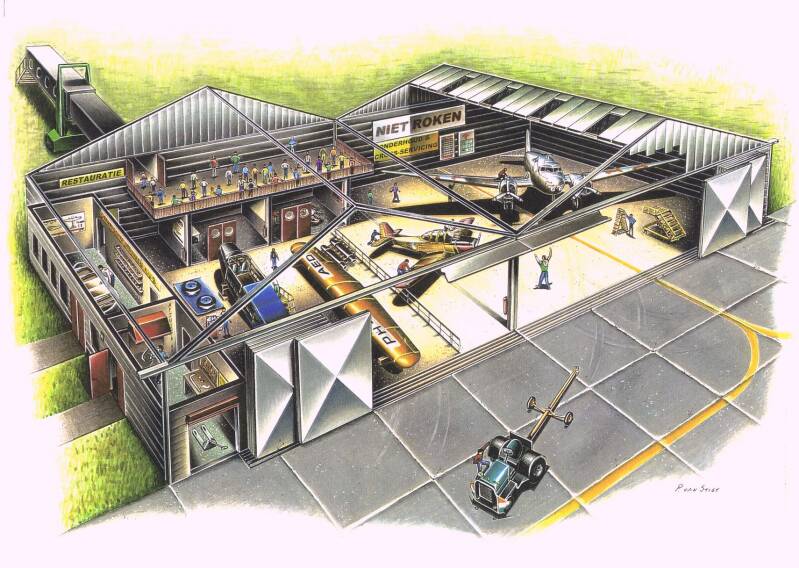

To top it all off and bring it all together, start producing a full-color illustration in which all aspects of shape and lighting according to the rules of 'perspective'. The sky is the limit. The artist is free to dream up any object. For example a fantasy aircraft as shown below, set in a dramatic background. All stitched together in order to bring your 'paper tiger' to life. Programs in this case used for this image are ArtRage for enhanced drawing and painting and Photoshop for initial drawing, painting, airbrush and filtering in tones and colors.